Last updated: 10/12/2025

Enforce front-of-pack labelling

Enforce the provision of interpretative front-of-pack labelling on retail packaging

- Moderate impact on obesity

A percentage estimate of how much the policy would reduce national obesity rates

- Relative reduction in obesity prevalence: 3%

- Very high evidence quality

A rating of the strength of evidence, accounting for both reliability and validity of the evidence

- Reliability and validity rating: 5/5

- Low cost to governments

Cost to UK and devolved governments over 5 years

- Costs to governments over 5 years: £18m

- Benefit to governments per year: £2bn

What is the policy?

This policy relates to mandating the provision of front-of-pack labelling (FOPL) on retail packaging. This policy would move the UK from a voluntary FOPL to a mandatory FOPL. Front-of-pack nutritional labelling is a policy tool used internationally to promote healthier food consumption. The aim of labelling is to influence consumers at the point of purchase to choose food products with a better nutritional profile, and to incentivise food manufacturers to improve the nutritional quality of products through reformulation.

Nutritional information can be mandated on packaging in various formats. There are two major categories of food labels: interpretative (graphic, easily recognisable simplifications of nutritional information, like traffic lights or star systems) and non-interpretative (numeric summaries that require customers to interpret themselves – usually back-of-package). This policy is centred around interpretative FOPLs in general, without focusing on any specific type exclusively.

Recent context

Whilst it is mandatory for nutritional information to be displayed on the back of all food packaging in the UK, there is not currently any mandatory FOPL in the UK, including in Scotland or Wales.

As FOPL is voluntary, individual businesses can decide on which foods the information will be most useful to consumers. Across the UK, many businesses that opt to provide FOPL use the multiple traffic light labelling system. A four-nation public consultation on FOPL took place in 2020, led by the Department of Health & Social Care.

In its strategy Healthy Weight, Healthy Wales, the Welsh government states that they will: ‘Seek out and harness further opportunities by working across the UK, including enhancing front-of-pack labelling to best support positive food choices’.

In Scotland, the Diet and Healthy Weight Delivery Plan outlined intentions to urge the UK government to push for mandatory front-of-pack labelling, highlighting that it would help consumers easily identify healthier and less healthy foods.

There are many different types of FOPL that have been created, and various formats are used internationally with mandatory or voluntary implementation.

Case studies

Nutri-Score, France

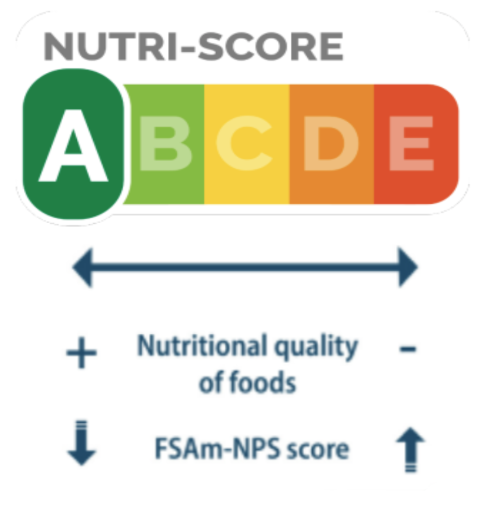

Nutri-Score labelling was developed upon request from the French Ministry of Health, with French public authorities officially recognising Nutri-Score as the front-of-pack labelling system for food products in October 2017. Nutri-Score is a simple interpretative nutrition label using five colours to classify food products: from category A, indicating higher nutritional quality, to category E, indicating lower nutritional quality. See example image below, reproduced from Dubois et al. (2021).

It was gradually implemented, with 70 food producers voluntarily adopting Nutri-Score by July 2018, rising to 450 producers (representing 50% of the market share) by July 2020. Santé Publique France, the body in charge of Nutri-Score’s implementation, conducts an annual study to track awareness, support and self-declared impact of Nutri-Score on purchasing behaviours across the population. By 2019, 57% of the sample declared they had changed at least one purchasing behaviour due to the measure. However, there is the possibility of publication bias in some of the reports of Nutri-Score’s effectiveness. Specifically, our Expert Advisory Group (EAG) advised that studies run by the label’s developers tend to find favourable results compared to independent studies.

Nutri-Score has been adopted across Europe, including in Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Portugal, Luxembourg, Spain and the Netherlands. The Nutri-Score algorithm was updated in 2023, and will gradually be implemented, starting in France in 2025.

Warning labels, Chile and wider Latin America

Warning labels are a simple interpretative nutrition label applied to food and drink products that exceed thresholds for energy content and various risk nutrients. They typically state things like ‘high in’, ‘excessive in’ or ‘not recommended to children’.

Chile was a pioneer of this approach, with a law on mandatory nutritional warning labels in 2016. The law required packaged food exceeding nutrient-specific thresholds to show a black octagonal warning on the front of packaging with the message ‘high in’. See example image of warning labels, reproduced from the Chile Ministry of Health 2019.

Mexico followed suit in 2020, also utilising black octagonal warning labels, bearing the message ‘excessive in’ if products exceed thresholds for sugar, sodium, saturated fats and calories, and a rectangular warning message if a product contains trans fats. Messages saying ‘not recommended to children’ must also be displayed if a product contains non-nutritive sweeteners or caffeine. Products carrying 1+ warning labels cannot include any marketing strategies directed towards children (eg, cartoon characters, interactive elements on the packaging).

Warning labels have extended throughout Latin American countries, with legislation and signage varying. Some of these can be seen in the map, reproduced from the Obesity Evidence Hub (last updated 27 July 2023). In some of these countries, labelling legislation is integrated with other policies, eg, foods with warning labels cannot be sold in schools in Chile, Argentina and Peru.

Considerations for implementation

Mandating FOPL would require legislation to establish new labelling requirements on food businesses (in each of England, Wales and Scotland). It would also need new guidance from the UK and devolved governments for food businesses on labelling.

Regulation commencement timeframes would need to provide sufficient time for businesses to reprint packaging and make their product portfolio compliant with legislation. As with the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), allowing sufficient lead-in time may also encourage businesses to reformulate products. Manufacturers may opt to improve products’ nutritional content in order to make product labels look more favourable to suppliers and consumers.

Once in force, the policy would also require monitoring and enforcement by a named agency (for example, the Food Standards Agency).

Estimating the population impact

We estimated that this policy would reduce the prevalence of adult UK obesity rates 3%

Estimating the per-person impact

We estimated that this policy would reduce average daily calorie intake by approximately 7.4 kcal per person

The intervention modelled interpretative FOPL but does not include warning labels. We did not purposefully exclude warning labels, but rather used the best available literature for interpretative FOPL, which happened not to include them.

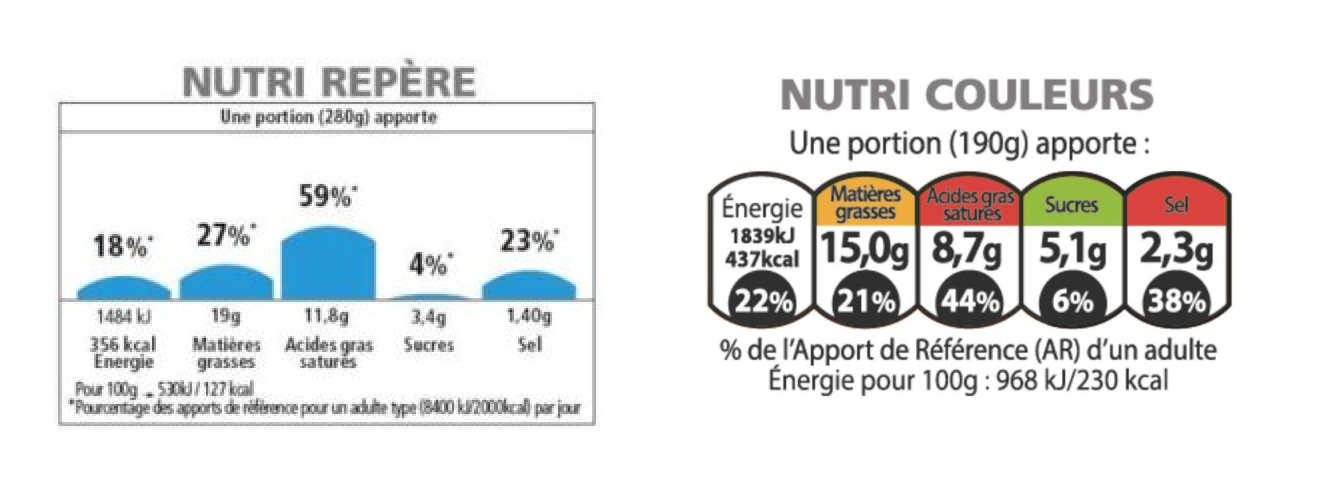

In the Cochrane Review conducted by Clarke et al. (2025), two types of FOPL were used for meta-analysis: Nutri Repère and Nutri Couleurs. These were selected as they met the intervention criteria of being forms of calorie/energy labelling. See example images of the labels below, reproduced from Dubois et al. (2021).

We estimated the impact on daily calorie reduction using the Cochrane review Clarke et al. (2025). We extracted the meta-analysis results from the most appropriate subset of studies included in this review (ie, those with the highest potential for real-world generalisability, focused on stores as a setting, ie, where food would be pre-packaged). Specifically, we used the meta-analysis in Analysis 1.2 (pg. 89), Comparison 1.2.2 (‘Stores’), with results based on two eligible comparisons of Dubois et al. (2021).

This study found that labels were effective in reducing the purchase of calories by 0.05 SMD in comparison to no labels. This is equivalent to a 0-54 kcal reduction in energy intake per person per day as published in Hollands et al. (2015). For the modelling, we assume an average reduction of 27 calories per person (adult) per day.

A series of methodological adjustments were applied to refine this estimate. First, our analysis corrected for underreporting in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey by applying a 1.32 multiplier. This is based on a 32% underestimation of calorie intake reported in a doubly labelled water study on NDNS data conducted by ONS. This resulted in increasing the effect to 35.6 kcals. The estimate was then adjusted to exclude out-of-home consumption (estimated to contribute 11% to our daily calories on average) and non-packaged food (estimated to account for, on average, 7% of calories from retailers). To reflect real-world implementation, the effect size was further adjusted for the current baseline FOPL coverage of 66% by multiplying by 0.34, yielding 10.01 kcals, and finally incorporated a 23% compensation effect. This systematic adjustment process resulted in a final input of -7.4 kcals per person per day, representing our estimate of FOPL’s potential impact on daily energy intake.

The impact of product reformulation was not included in the modelling due to a lack of quantitative evidence on this. However, we do anticipate that reformulation is a possible mechanism for calorie change following mandatory FOPL. Some manufacturers are likely to reformulate their products in order to improve their labels, which could have a further impact on obesity. This is corroborated by evidence from Chile – mandatory warning labels were implemented there in 2016, leading to ~15% of “high in” products being reformulated according to a 2021 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Although it was not quantitatively modelled in this policy, the blueprint toolkit does have a policy on incentivising reformulation of HFSS.

Estimating the population reach

In our analytical model, we applied the effect sizes to people living with overweight or obesity. For adults, that is people aged 18 or above with a BMI of 25+. We are in the process of estimating the impact of this policy on children and will update our findings as soon as possible.

Changes in the prevalence of people living with obesity

Table 1 shows the percentage reduction of adults and children moving from BMI≥30 to a healthier BMI category following the introduction of a mandatory front-of-pack labelling. We are in the process of modelling the impact on children and will update findings upon completion.

| Adults (England and Wales) | Children 5-18 (England and Wales) | Adults (Scotland) | Children 5-18 (Scotland) |

| 2.6% | In progress | In progress | In progress |

Cost and benefits

Cost over 5 years

We estimated that this policy would cost the governments approximately £18 million over five years

Table 2 below shows a breakdown of costs. The direct costs to the governments of monitoring and enforcing is estimated at approximately £1.4 million per year and the cost of running a social marketing campaign is estimated at £2.2 million per year (totalling £18 million over five years). The costs to the food industry are estimated at approximately £2 million in the first year for familiarisation and around £4 million per year for three years to change the product labels. This policy would require the implementation of mandatory healthy food sales reporting, the costs of which are not included in this breakdown and are included as a separate policy: Data collection on healthiness of product portfolios.

| Group affected | Cost | Horizon | Detail |

| Costs | |||

| Government | £1.4m | Annual (5 years) | Monitoring and enforcement costs |

| Government | £2.2m | Annual (5 years) | Social marketing campaign |

| Industry | £2m | One-off | Familiarisation costs |

| Industry | £4m | Over 3 years | Implementation costs of changing product labels |

Total annual benefit

We estimated that this policy would have an annual benefit of approximately £2 billion

Using analysis conducted by the Tony Blair Institute and Frontier Economics, we estimate this policy would result in benefits of £2 billion per year on average. Approximately two-thirds of this saving would benefit individuals (via quality-adjusted life years and informal social care). The remaining third relates to savings that benefit the state via NHS treatment costs, productivity and formal social care. See our Technical Appendix for more information about the cost breakdowns.

Behind the averages: impact on inequalities

While experimental, non real-world evidence suggested FOPL to be an equitable approach (eg, Pettigrew et al.’s (2023) study), a closer look at the results show that while nutritional understanding was improved across participants of 3 income tiers after exposure to FOPL, the effect on actual food choices were generally much smaller.

As explored in our inequalities blog, policies that require individuals making different choices are less likely to have an impact without addressing environmental drivers of unhealthy behaviours.

Rating the strength of evidence

We asked experts working in the fields of obesity, food, and health research to rate the strength of the evidence base for each policy, taking into account both reliability (size and consistency) and validity (quality and content) of the evidence. Policies were rated on a Likert scale of 1-5 (none, limited, medium, strong, and very strong evidence base). The Blueprint Expert Advisory Group rated this policy as having a Very Strong evidence base.

Restrict advertising of HFSS products

Implement a 2100-0530 watershed for TV and online advertising, alongside strict limitations on online paid advertisements, as well as prohibiting all HFSS advertisements on public transport, including bus stops, train stations, and tube stations (via national regulation)