Last updated: 10/12/2025

Implement pharmacotherapy using tirzepatide

NHS rollout of tirzepatide as per the implementation proposal in the 2024 NICE guidance

- Very low impact on obesity

A percentage estimate of how much the policy would reduce national obesity rates

- Relative reduction in obesity prevalence: 0%

- Reduction in obesity class 3: 19%

- Very high evidence quality

A rating of the strength of evidence, accounting for both reliability and validity of the evidence

- Reliability and validity rating: 5/5

- Very high cost to governments

Cost to UK and devolved governments over 5 years

- Costs to governments over 5 years: £1.6bn

- Benefit to governments per year: £2bn

What is the policy?

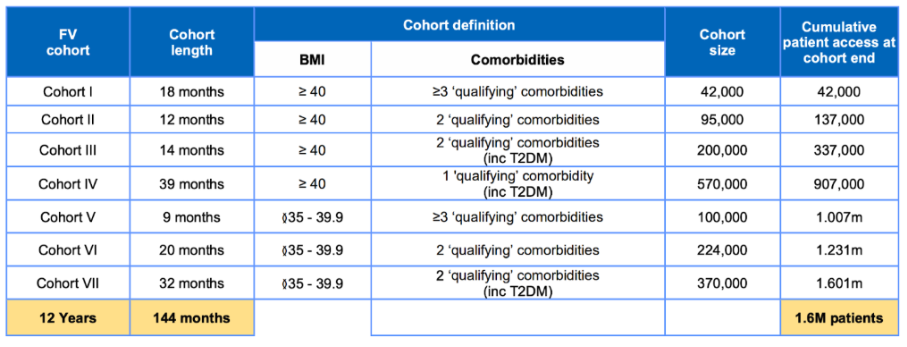

This policy lays out a proposal by NHS England to rollout the weight-loss drug tirzepatide in England, following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendation. Tirzepatide has been shown to be effective for addressing obesity. Released in 2024, the NICE implementation guidelines recommend a phased rollout based on BMI and comorbidities. Under the proposal, cohort prioritisation begins with those patients with the highest clinical need (in this instance, people living with a BMI ≥40 and multiple obesity-related comorbidities), and then it slowly extends to those with fewer comorbidities and in relatively lower obesity BMI groups. NICE specifies a maximum implementation period of 12-years to complete the full rollout. However, consistent with other policies in the blueprint toolkit, this policy page shows the effect of the policy over a 5-year time horizon, ie, the first 5 years of the rollout (see the section ‘Population Impact’ for detailed methods).

The impact of other weight-loss drugs, semaglutide and liraglutide, was separately modelled in a blueprint policy page here. However, these two policies are not directly comparable as they differ in roll-out mechanism (notably prioritisation and number of people treated) and treatment duration. See the methodology section for details.

Recent context

GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) weight-loss medications are still relatively new, but are becoming increasingly popular to manage obesity. They can help in the process of losing weight, and have been shown to be effective as part of a weight management plan for those who struggle with losing weight.

Tirzepatide is a weight-loss medication, recently approved by NICE. It works in two ways – firstly as a GLP-1 receptor agonist, but also as a GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide) receptor agonist, unlike other previously released weight-loss medications. In clinical trials, it has been shown to produce greater weight loss and improve insulin sensitivity to a greater extent compared to semaglutide.

Tirzepatide is recommended by NICE for patients who have an initial BMI of at least 35 kg/m2 and at least 1 weight-related comorbidity. These conditions include: hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, cardiovascular disease, prediabetes, and type 2 diabetes.

NHS England (NHSE) has released interim commissioning guidance to follow the NICE recommendations of phasing the rollout of tirzepatide in England.

In Wales and Scotland, NHS funding is devolved and influenced by the Barnett formula, which adjusts their budgets based on changes in England’s public spending. In Wales, weight-loss medication, including tirzepatide, is only available through specialist weight management services. In Scotland, the Scottish Medicines Consortium has approved tirzepatide for restricted use in NHS Scotland.

Case studies

Provision of GLP-1 drugs via the NHS, UK

Semaglutide, often marketed as Wegovy, is a GLP-1 drug that has been available through the NHS since September 2023. In 2025, it was estimated that approximately 1.4 million people in the UK access GLP-1’s predominantly through private online pharmacies every month. It is thought that, of all people accessing weight-loss medication in the UK, that the vast majority access them through private services.

There is high demand for these medications and supply issues have affected the rollout. In the summer of 2023, there was a global shortage of semaglutide, with supplies having to be reserved for those already using the medication. It is now reported that these supply issues have been resolved.

In Scotland, the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) granted approval for the drug, but not all health boards had a weight management support model to support the recommendations, limiting the rollout. In March 2025, the BBC reported that the waiting list outnumbered those currently being seen by specialist weight services.

The high waiting lists may be exacerbating health inequalities in the UK. Low-income families are already disproportionately at risk of obesity, and the limited access may be widening the gap in health outcomes between those who can afford private healthcare and those who rely on state healthcare.

In addition, counterfeit versions of semaglutide were identified in the UK in June 2024. A warning was issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) with these products posing a potential risk to health.

Considerations for implementation

Implementing a phased rollout for weight-loss medications requires multiple considerations, especially given the differences in healthcare governance across the devolved nations and the differences in accessibility to specialist weight management services.

- Funding mechanism: The proposed timeframe for NHS England rollout is long (up to 12 years), and funding could change during this time period, impacting the rollout.

- Supply issues: Implementing this policy must also address potential supply issues. The increased demand for GLP-1 receptor agonists for weight loss could affect the availability of these drugs for people with diabetes who rely on them for blood sugar control. Investment in NHS infrastructure and additional staff would be required for successful implementation.

- Weight regain: Studies indicate that patients may regain weight if they discontinue the medication. This highlights the need for long-term management plans and continuous monitoring to maintain the benefits of the treatment. In the present policy page, no weight regain is modelled as it is assumed that people would stay on the drug for the whole modelling time horizon, given there is no stopping rule under the current guidance. In reality, some people are likely to cease medication due to side effects.

- Unknown long-term effects: The long-term safety and efficacy of weight-loss medications such as GLP-1s remain under investigation. Continuous research and post-market surveillance will be essential to understand the potential long-term health impacts and to update treatment guidelines accordingly.

- Counterfeit medications: Fake GLP-1 medications have hit the UK market previously, and could cause harm to those who take them. It is important that procedures are put in place to prevent this from happening again, especially if demand increases for medications like tirzepatide.

Estimating the population impact

We estimated that this policy would reduce the prevalence of adult UK obesity rates by approximately 0% overall, but it would reduce obesity class 3 by 19%

This policy has a low impact on obesity (BMI ≥ 30) reduction because the first 5 years of its 12-year rollout (as captured in the standard 5-year time horizon used in the blueprint toolkit) specifically target those living with obesity class 3 (BMI ≥ 40), bringing them down towards a lower obesity class, but still living with obesity. While the funding and access to medication is limited, those with the greatest clinical need should be prioritised. This will have a significant impact on improving the health of those people, as they move to milder forms of obesity, even if it may not result in them achieving a healthy weight. The positive effect of reduced obesity class 3 prevalence is instead captured in our benefit estimate. This section details the methodology we adopted.

Estimating the per-person impact

- Tirzepatide demonstrates an 18.5% weight loss for those living without type 2 diabetes and a 13.8% weight loss for those living with type 2 diabetes. We use treatment regimen estimates in our modelling because this accounts for dropouts and discontinuation from treatment and is likely to be representative of the real-world effect of tirzepatide.

- We apply these reductions to the baseline body weight of individuals based on their diabetes status. In our modelling, all weight loss from tirzepatide is experienced in the first year of receiving the drug, after which people’s weight plateaus. This assumption aligns with findings from the SURMOUNT-1 Phase 3 trial, where patients experienced a weight plateau in 72 weeks, with the majority of the weight loss occurring within 52 weeks. Moreover, it also shows that individuals would not indefinitely lose weight for the period they receive tirzepatide.

- With the NICE and NHSE guidelines not prescribing a stopping rule for the drug, we assume that those receiving the treatment would stay on it for our five-year modelling period. Therefore, during this period, they do not experience any weight regain, or in other words, individuals receiving the treatment maintain their weight loss for our modelling period. This differs from the previous GLP-1 policy modelled in the blueprint toolkit, which included weight regain as individuals stopped taking the drug after 2 years of treatment.

Estimating the population reach

We apply the effect sizes to adults who meet the current NICE guidelines for prescribing tirzepatide via the NHS. NICE and NHSE guidelines use a cohort-based allocation to determine eligibility to receive the treatment over a 12-year period. The long-term plan is to reach 3.4 million individuals. For our five-year impact modelling, we follow the same approach by allocating individuals into cohorts based on the eligibility criteria for each cohort. Over the five years, approximately 580,000 eligible individuals received the drug, of which 406,000 are estimated to take up the offer. The eligibility criteria for each cohort are in table 1 below.

Qualifying comorbidities include atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obstructive sleep apnoea, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

For each year in our model, we use a random weighted sampling approach to select the required number of individuals from a pool of all eligible individuals in a particular year. Please see the technical appendix section called ‘Handling policies that applied to specific populations‘.

Changes in the prevalence of people living with obesity

| Adults (England and Wales) | Children (England and Wales) | Adults (Scotland) | Children (Scotland) |

| 0% | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Cost and benefits

Cost over 5 years

We estimated that this policy would cost the governments approximately £1.6 billion over five years

We source the costs for implementing this policy from the NICE and NHSE implementation plan. We estimate the total costs using the cost per slot specified in Table 1 and the number of projected slots as per Table 4 to estimate the five year costs of this rollout.

| Group affected | Cost | Horizon | Detail |

| Costs | |||

| GP-led cost | £570m | Over 5 years | Cumulative cost to NHS for delivering GP appointments and wraparound care including nurse time, blood tests, pharmacist support, dietician sessions, psychological support sessions, and onward care |

| Drug cost | £994m | Over 5 years | Cumulative cost to NHS of tirzepatide for 406,000 people over a five year period |

Total annual benefit

We estimated that this policy would have an annual benefit of approximately £2 billion

Using analysis conducted by the Tony Blair Institute and Frontier Economics, we estimate this policy would result in benefits of £2 billion per year. Approximately two-thirds of this saving would benefit individuals (via quality-adjusted life years and informal social care). The remaining third relates to savings that benefit the state via NHS treatment costs, productivity and formal social care. See our Methods page for more information about the cost breakdowns.

As the blueprint toolkit models cost savings from reductions in overall obesity prevalence (BMI ≥ 30), our estimates normally focus on people no longer living with obesity. However, due to the roll-out plan for this policy, most of the impact in our five-year modelling period will be among those living with obesity class 3 (BMI ≥ 40). In our modelling, participants would experience weight loss of approximately 20 kg on average, but did not move out of the obesity BMI class. To recognise the benefit from the significant weight loss achieved through tirzepatide, we apply the same monetary value used for reductions in overall obesity prevalence to the proportion of people experiencing weight loss. We believe that this approach provides a more accurate estimate of the policy’s benefit during the early roll-out period and ensures that the gains from reducing obesity class 3 are fully recognised.

Behind the averages: impact on inequalities

Financial inequalities: Most people are only able to access weight-loss medications through the NHS, and are not in a financial position to pay for private access. The phasing of access to tirzepatide will hopefully help to mitigate access and supply issues for those most in need of weight-loss medication, but some people may have to wait to become eligible. Those who are able to afford the medication through private healthcare may access the weight-loss medication that way. This could exacerbate health inequalities in the short term, with the wealthiest able to access the treatments sooner than the poorest, while it is those living in higher-deprivation areas that are more at risk of obesity. The latest data for England shows the social gradient strongly with the most deprived areas having the highest rates of obesity (37%) and the least deprived the lowest (20%).

Other health conditions: Previously, the NHS faced prolonged supply challenges with GLP-1 receptor agonist medications, which are used to manage blood glucose levels in people with type 2 diabetes. This shortage was partly driven by a significant increase in off-label prescriptions of semaglutide for weight loss, resulting in demand that exceeded supply. These supply issues have since been resolved, and the NHS’s phased rollout of tirzepatide may mitigate against this recurring, but it is a consideration for health inequalities, given these weight-loss medications are also key medications to manage diabetes.

Rating the strength of evidence

We asked experts working in the fields of obesity, food, and health research to rate the strength of the evidence base for each policy, taking into account both reliability (size and consistency) and validity (quality and content) of the evidence. Policies were rated on a Likert scale of 1-5 (none, limited, medium, strong, and very strong evidence base). The Blueprint Expert Advisory Group rated this policy as having a Very Strong evidence base.

Extend access to pharmacological interventions

Provide an extra £500 million of ring-fenced funding per year to increase access to NICE recommended weight-loss treatments (liraglutide and semaglutide)